Ancient China has produced many remarkable architectural buildings, including the world-renowned Great Wall, the Forbidden City, and the mausoleums— to name just a few.

As a professional in the architecture and construction industry, I am consistently drawn to the wisdom embedded in ancient Chinese buildings. So, I have decided to create a series on this subject.

As a Hakka person, I will begin this series by exploring a rather unique type of building: the Hakka Tulou.

Rammed Earth Buildings: A Thousand-Year Hakka History Within a Hakka Tulou

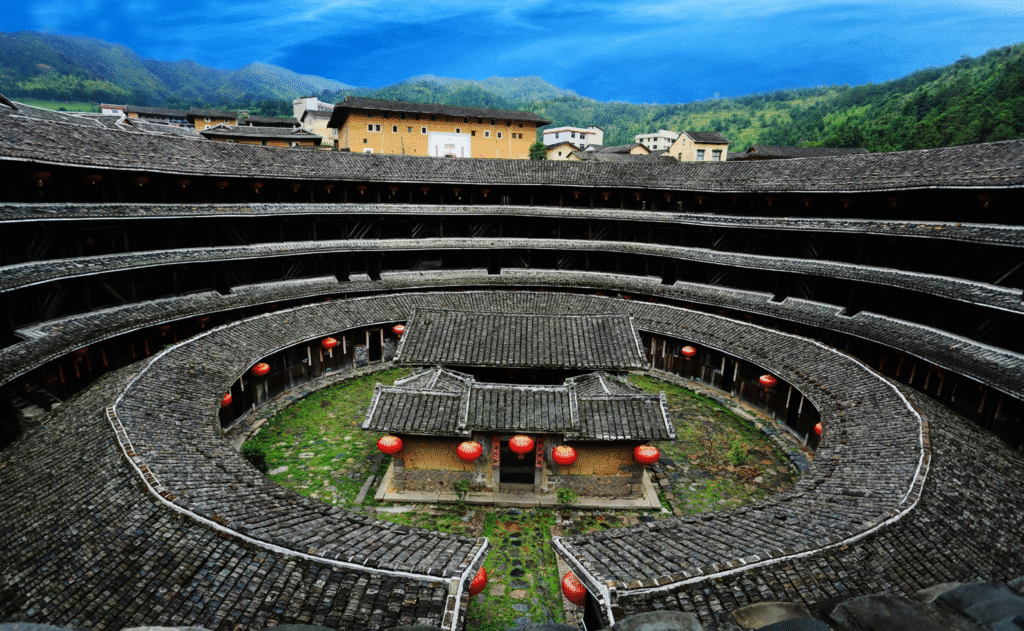

In the verdant mountains of southwestern Fujian, a colossal architectural style stands silently. Round or square, big or small, some 3,000 in numbers. They resemble sculptures of the earth, bearing witness to six centuries of Hakka wisdom. This is the Hakka Tulou (earthen buildings) —a three-dimensional epic written with loess, bamboo, wood, and pebbles.

The Mark of Migration: Hakka Tulou is the Architectural Answers from "Guest" to "Home"

The Hakka people’s history is one of migration. Starting in the Western Jin Dynasty (266-316 AD), gentry from the Central Plains fled war and migrated south in five large waves, eventually settling in the mountainous regions bordering Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi provinces. The word “guest” reflects both their wandering and their resilience.

Yet this new home brought many dangers: high mountains, dense forests, limited resources, frequent conflicts with local inhabitants, and the incursions of Japanese pirates during the Ming (1368–1644 AD) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties. Amid this persistent insecurity, the Tulou emerged—not only as dwellings but also as fortresses. Through architecture, the Hakka people answered the challenges of survival with remarkable ingenuity.

A Living Heritage: Hakka Tulou From Fortress to Home

When visitors enter the Hakka Tulou today, they feel the vibrant atmosphere of daily life. Elders sit by the ancestral hall, children play in the courtyard, and smoke rises from hundreds of stoves—this 600-year-old “fortress” continues to serve as a warm home.

UNESCO describes the Fujian Hakka Tulou as “a historical testament to the traditional culture of kinship and clan-based living in the East.” Tulou represents not merely an architectural style but a declaration of survival by the Hakka people: they built the strongest homes from the simplest materials and preserved the most precious human connections with united hearts.

These silent, round giants still stand in the mountains of southwestern Fujian, telling the world an enduring story of resilience, wisdom, and inheritance—how an ethnic group keeps its cultural bloodline alive in the most challenging environments. Every inch of rammed-earth wall embodies the Hakka people’s millennia of wandering, perseverance, and hope.

Unlike other magnificent ancient buildings, which were mostly constructed by royal or government institutions, the Tulou were built by the most grassroots, even marginalized, Hakka community. This makes the marvellous Hakka Tulou all the more admirable

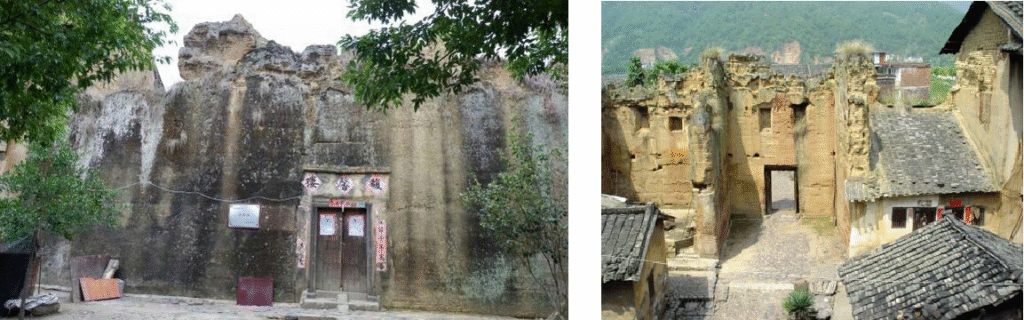

The Layers of Time: A Construction History Spanning Seven Centuries

The oldest existing Tulou originated during the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907). For example, builders constructed the Fuxinlou in 769 AD, and it still serves as a residence today. Builders ushered in the golden age of Tulou construction during the late Ming (1368 to 1644) and early Qing (1644 to 1912) Dynasties, and many are still in use today. The social upheaval of this period ironically inspired the creation of masterpieces in defensive architecture.

- Chengqilou (built during the Chongzhen era of the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644) and completed during the Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty): “Four stories high, four concentric circles, and four hundred rooms in total,” this structure housed over 600 people at its peak

- Eryilou (built in 1740): Pushing ventilation, lighting, and defence to their limits.

- Zhenchenglou (built in 1912): This fusion of Chinese and Western styles earned the title “Prince of Tulou.”

The Hakka Tulou evolved from the simplicity of the Ming Dynasty to the grandeur of the Qing Dynasty and the innovations of the Republic of China, reflecting the dynamic progress of the Hakka people.

A Miracle of Technology: Hakka Tulou is An Eternity Born from the Soil

Hakka Tulou (earthen buildings) use extremely simple materials—red soil, fir wood, bamboo strips, and pebbles—yet these resources create an architectural marvel: Rammed earth construction lies at the core.

Builders use the “rammed earth method”: they pour a mixture of loess, lime, and sand into moulds and ram it layer by layer. To enhance toughness, they add brown sugar water, glutinous rice paste, and even egg white. This process produces walls 1–2 meters thick that offer strength, insulation, fire resistance, and earthquake resistance. Many Hakka Tulou have stood tall for centuries, enduring wind, rain, and even earthquakes.

Structural wisdom is evident everywhere:

- Circular design with no blind spots, facilitating crossfire during defense

- Enclosed base of the outer walls, with small windows at higher points for observation and firing

- The single main gate is made of thick wood covered with iron sheets, with a water injection hole behind the door for fire prevention

- The internal “three halls and two wings” layout, symmetrical along the central axis, with distinct layers

A Vertical Clan Universe: Hakka Tulou is a Building and a City

The grand scale of Hakka Tulou stands out as their most striking characteristic. The largest round buildings measure more than 90 meters in diameter and cover several thousand square meters, resembling miniature vertical cities. This scale reflects the Hakka people’s kinship-based social structure—only a tightly united family could ensure survival in unfamiliar environments.

A large earthen building can house 200 to 800 people, all sharing the same clan and surname. For example, at its peak, Chengqi Building accommodated over 80 households and more than 600 people, while Huanji Building once housed over 400 people. Such high-density settlements are extremely rare in the history of vernacular architecture worldwide.

The spatial layout is highly symbolic:

- Core Ancestral Hall: Located at the end of the central axis, it houses ancestral tablets and serves as the spiritual centre.

- Vertical Zoning: The first floor houses the kitchen and dining room; the second floor is for storage; and the third and fourth floors contain bedrooms.

- The Concept of Equality: Builders designed the rooms in the round building to be the same size and face the same direction, reflecting family equality.

- Self-Sufficient System: Residents equipped Tulou with wells, granaries, livestock pens, schools, and ancestral halls, enabling long-term self-sufficiency.

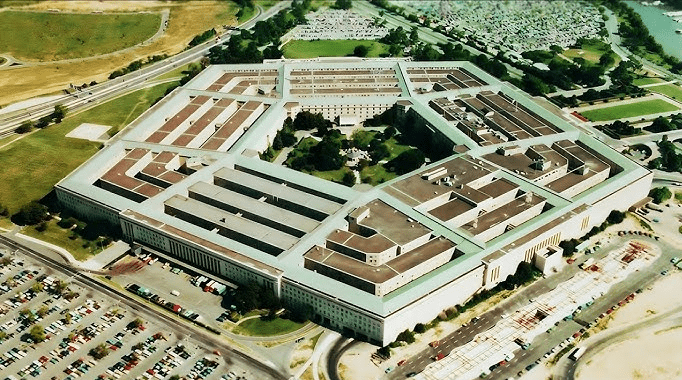

A Cold War-era blunder about the Hakka Tulou

During the height of the Cold War in the 1960s and 70s, US intelligence agencies photographed China’s southeastern coast with spy satellites and discovered many large, circular, and square buildings nestled in the mountains of western Fujian Province.

On satellite imagery, these clusters of buildings—with their unusual shapes and large-scale distribution—looked like massive underground nuclear missile silos or nuclear reactors.

This misjudgement initially alarmed US officials, who believed China was deploying nuclear weapons facilities on a large scale in the region

Because satellite imagery could not reveal the interiors of these buildings, the US sent personnel to investigate on-site after China and the US established diplomatic relations in the 1980s, following China’s reform and opening.

According to records and folklore, around 1985, CIA officials or researchers entered Longyan and Yongding in Fujian Province disguised as tourists or scholars.

When investigators entered these buildings, they found no missiles inside—only hundreds of traditional Hakka dwellings. These so-called “missile silos” turned out to be centuries-old masterpieces of Hakka Tulou architecture

This humorous misunderstanding on the national security marks the beginning of our new series on ancient Chinese architecture. I will continue to cover more in future articles. Please let me know if you would like me to feature a specific type of ancient Chinese architecture.