What does the Chinese language mean and represent to non-Chinese people? Many people may associate the Chinese language with Mandarin, although it is the official language for China. However, Chinese language encompasses much more than just Mandarin. There are more than ten different Chinese dialects system, all spoken primarily by the Han people.

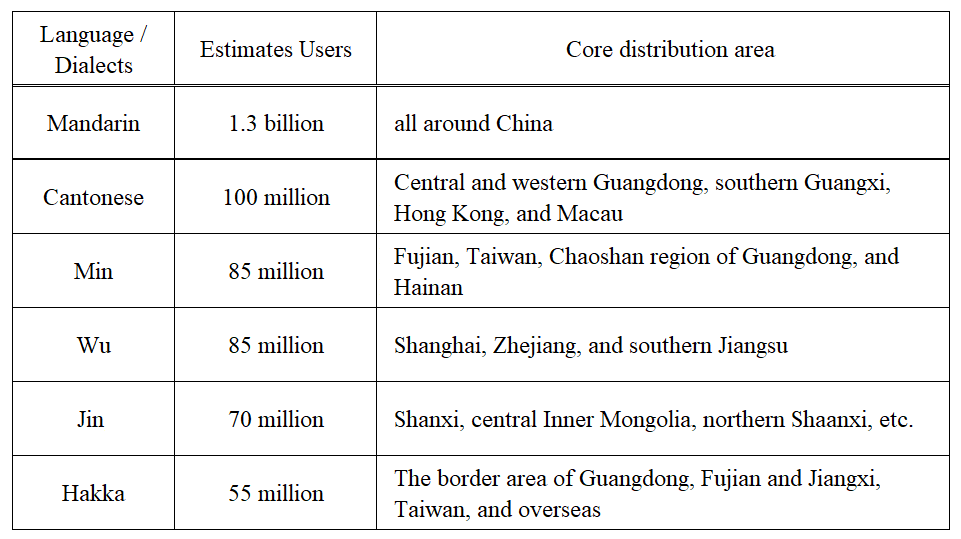

Today, we explore Mandarin and the top five most widely spoken Chinese local dialects: the Cantonese, Min, Jin, Wu, and Hakka. We examine the history and characteristics of these languages and provide examples to enhance your understanding.

A Breakdown of the 5 Most Popular Chinese Dialects

As the table shows, each of the top five contenders boasts over 50 million users, and Cantonese reaches up to 100 million users.

We need to understand a basic concept about these five local dialects. Each dialect forms a language system with further branches. Usually, branches under a dialect share similarities and people can understand each other across them. However, some branches have developed so distinctly that even speakers of the same dialect may find them difficult to understand.

A basic understanding of this dialect is essential, especially for anyone who wants to learn more about Chinese culture

Mandarin Chinese(普通话/华语): The Official Language of China

Mandarin Chinese—modern standard Chinese based on the Beijing pronunciation and Northern Mandarin—originated and evolved over thousands of years of Chinese civilization.

Mandarin originated from the “elegant speech” of the pre-Qin period, which served as the earliest official language. As the political center shifted northward over time, Northern dialects formed the basis of the “Mandarin” system, which gradually became the official language during the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties.

In the early 20th century, the New Culture Movement popularized vernacular Chinese, and in 1955, the Chinese government officially established “Putonghua” (Standard Mandarin) as the national common language and promoted it nationwide.

Mandarin as the official language of China, has developed Hanyu Pinyin Scheme, the standard for the pronunciation and sound. Its four-tone system gives the language musical beauty; the writing system, based on Chinese characters, combines pictographic and ideographic functions; and its grammar emphasizes flexibility and conciseness, independent of morphological changes.

Today, as one of the United Nations’ working languages, Chinese serves as both the world’s most widely spoken language and a key carrier of Chinese culture, promoting the global dissemination and exchange of Chinese civilization.

Mandarin exhibits regional characteristics

Although Mandarin follows systematic grammar and writing conventions, but regional dialects and local influences still shape its distinctive speech characteristics across China. As a result, my non-Chinese friends often struggle to understand media interviews, even when they recognize the language as Mandarin.

Consider English in the United Kingdom as an example. We recognize Received Pronunciation as the formal version; it sounds elegant and smooth. Personally, I prefer London Cockney English because it feels raw and friendly. The Irish accent often sounds rhythmic and can challenge listeners, though I enjoy it very much. Let’s not forget the famous Scottish accent.

This example may not perfectly illustrate the accent differences in Chinese Mandarin, but I believe you get my point.

Dedicate a Song as an Example

After much thought, I realized that a song provides an excellent way to help you become familiar with a new language. I have chosen a song for each dialect to enrich your experience.

For Mandarin, I dedicate this song to my late father-in-law, as Teresa Teng was his favourite artist.

The Cantonese(粤语): The Language of Hong Kong and Guangdong

Cantonese, also known as the Guangdong dialect, has a long history as a Chinese dialect. It originated during the Qin and Han dynasties, when immigrants from the Central Plains migrated south to the Lingnan region. These settlers blended Old Chinese with the local Baiyue languages, creating the foundation of Cantonese. By the Tang and Song dynasties, Cantonese had matured and developed steadily, thanks to Guangzhou’s crucial role as the starting point of the Maritime Silk Road.

Cantonese historically served as one of the official languages of ancient China and retains many features of Old Chinese. People mainly speak it in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, and Macau, and it significantly influences overseas Chinese communities. Cantonese includes several branches. The Yuehai (Guangfu) dialect, originating from the Xiguan Pass of Guangzhou, sets the standard pronunciation. Other major branches, such as Siyi, Gaoyang, Wanbao, and Guinan, each have distinct pronunciation and vocabulary.

Cantonese most notably preserves all the Middle Chinese final consonants: -m, -n, -ng, -p, -t, and -k. It features a nine-tone, six-modal phonological system. Its vocabulary includes many classical Chinese terms, such as “食” (to eat) and “行” (to walk). In modern times, Cantonese has also absorbed extensive vocabulary from Western languages, giving it a unique and rich linguistic character.

For Cantonese, I selected a song by Roman Tam because he showcases the classic Cantonese tone and slang.

The Min Dialects(闽语): Hokkien, Teochew, and Fuzhounese

Min language forms an ancient and complex branch of the Chinese language family, with roots tracing back to the pre-Qin period. Repeated migrations of Han Chinese from the Central Plains to Fujian led Old Chinese to merge with the region’s indigenous languages, creating a unique Min language system during the Tang and Song dynasties.

Min language preserves the linguistic features of pre-Middle Chinese. Centered in Fujian, it spreads to Taiwan, southern Zhejiang, the Chaoshan region of Guangdong, Hainan, and, through overseas migration, to Southeast Asian countries.

Min language prominently preserves numerous Old Chinese phonological elements, such as pronouncing “pig” (猪) as ti and “tea” (茶) as te. Its initial consonant system features a “fifteen-tone” system, displaying a wide variety of literary and colloquial pronunciations.

Min dialect can be sub-divided into five branches: Eastern Min, Southern Min, Northern Min, Central Min, and Putian-Xianyou.

Min-nan dialect has the broadest influence and includes the Quanzhou-Zhangzhou, Chaoshan, and Southern Zhejiang subdialects. Eastern Min, represented by the Fuzhou dialect, features a complex tone sandhi system.

The branches differ so significantly that they can be mutually unintelligible, demonstrating the rich diversity of Chinese dialects.

For the Min dialect, I chose the song “Ai Pia Cia E Ya” (爱拼才会赢) because it is one of the most recognizable. More importantly, this YouTuber’s version features sound lyrics, making it easier if you want to learn to sing this song

The Wu Dialect(吴语): Language of Shanghai and Zhejiang

The Wu dialect, also known as the Jiangnan dialect, it history can date back to some 3,000 years ago. The ancient Yue language merged with Old Chinese and laid the foundation for Wu. As China’s economic center shifted south during the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties, as well as the Tang and Song Dynasties, Wu absorbed the refined sounds of Middle Chinese and gradually developed a unique dialect system.

Wu’s core characteristic is its complete preservation of the voiced initials of Middle Chinese, which gives its pronunciation an archaic quality. For example, speakers can still clearly distinguish the initials “帮,” “滂,” and “并.” Wu also features a rich system of continuous tone sandhi, which creates complex and rhythmic tonal variations in spoken language. Its vocabulary preserves many Old Chinese morphemes, such as “箸” (chopsticks) and “汏” (wash).

Geographical distribution and internal differences divide Wu dialects into several main sub-dialects: the Taihu sub-dialect (represented by Shanghainese and Suzhou dialects), the Taizhou sub-dialect, the Oujiang sub-dialect (represented by Wenzhou dialects), the Wuzhou sub-dialect (represented by Jinhua dialects), and the Chuqu sub-dialect. The Oujiang sub-dialect, in particular, exhibits significant internal variation.

The saying “the tone is different every three miles, and the pronunciation is different every ten miles” highlights the ancient and diverse linguistic features of Wu dialects.

I chose this Shanghainese song by Baobao Lin to represent the Wu dialect, because I only listen to hers when come to the Shanghainese song.

The Jin Dialect(晋语)of Shanxi and Inner Mongolia

First, I admit that I know very little about the Jin dialect. I have never encountered anyone speaking Jin with me, especially in our part of the world. Today’s topic gives me a good opportunity to learn more about Jin.

The Jin dialect is a Chinese dialect spoken in Shanxi Province and the surrounding regions. It originated in the heartland of the State of Jin during the Spring and Autumn Period and has absorbed significant influences from the languages of northern nomadic peoples.

Shanxi’s distinctive geography—enclosed by the Taihang Mountains to the east and the Yellow River to the west and south—has kept the region relatively isolated, which helped preserve many ancient linguistic features.

Jin dialect stands out among Northern Chinese dialects for retaining the entering tone, a feature that is now extremely rare. Speakers pronounce entering tone characters with a brief glottal stop “ʔ,” as in “一” (yī), “十” (shí), and “八” (bā). The dialect also features rich literary and colloquial pronunciation variations and includes many distinctive local words, such as those starting with “圪” (for example, “gē kù,” meaning to squat) and “谝” (piān, to chat).

Linguists divide Jin dialect into several main branches based on internal differences:

- The Bingzhou branch, represented by the Taiyuan dialect, forms the core area of Jin dialect.

- The Lüliang branch, represented by the Lüliang and Fenyang dialects, displays more complex linguistic features.

- The Shangdang branch, represented by the Changzhi dialect, retains more ancient pronunciations.

- The Wutai branch, represented by the Datong and Xinzhou dialects, covers a wide distribution area.

- The Zhanghu and Dabao branches are spoken in central Inner Mongolia and parts of Hebei and Shaanxi.

In summary, Jin dialect preserves the ancient entering tone and its unique linguistic style.

For the Jin dialect, I chose this Northern Shaanxi song for you. The emotion of this song matches my perception of the Jin dialect. I hope you will like it.

Hakka Dialect(客家话): The Language of "Guest Families"

Some readers may already know that I am Hakka. Today, I invite you to explore the Hakka dialect I use to communicate with my family.

In a nutshell, the term “Hakka” literally means “guest families.” This name highlights the true significance of our migratory people, emphasizing our long history of relocation and adaptation.

As a subgroup of the Han Chinese, Hakka emerged through a long history of migration. The ancestors of the Hakka originated in the Central Plains and, beginning with the Eastern Jin Dynasty, migrated south multiple times to escape war. They eventually settled mainly in the mountainous regions bordering Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong provinces. In this relatively isolated environment, their Classical Chinese blended with local indigenous languages, gradually forming the distinctive Hakka dialect during the Song and Yuan dynasties.

Because of its historical context, people hail Hakka as a “living fossil” of Classical Chinese, as it preserves many features of Middle Chinese. Phonetically, Hakka notably retains complete entering tone endings (-p, -t, -k) and six to seven tones. Its vocabulary abounds with archaic words, such as “I” (亻厓) (ngài), “eat” (食), and “black” (乌).

Although I am Hakka, I do not understand all the branches of the Hakka dialect. As is common in Chinese culture, things are often complex. The Hakka dialect has more than ten branches; some sound similar, while others have developed distinct differences. We must pay close attention to their speech, yet sometimes we may still not fully understand their words.

Today, I chose the song named “Hakka Essence” for you. It’s simple, unpretentious style reminds me of my late great-grandmother, who always lived simple and stayed down-to-earth.

Conclusion: Preserving the Rich Tapestry of Chinese Language and Its Dialects

In conclusion, China’s linguistic landscape forms a vibrant tapestry, woven from thousands of dialects. Mandarin binds the nation together, while regional tongues like Cantonese, Min, Wu, Jin and Hakka, add rich, colorful patterns that shape local identity and culture.

These five most widely used dialects system do more than facilitate communication. They preserve living history, art, and tradition. By preserving them, we safeguard a unique window into China’s diverse soul. When we understand this variety, we truly appreciate the depth and complexity of Chinese civilization.